The 7 Dwarfs: Engaged Team Players or Marginalized "Others"?

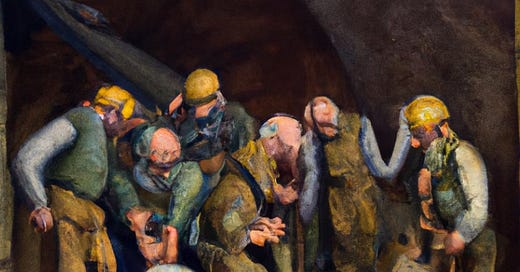

What looks like a degrading portrayal of outcasts has also been framed as an homage to American labor

The seven dwarfs… They work in a mine and live communally in a secluded cottage. For enrapt young minds, as well as grown-ups along for the ride, Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs delivers signals about both working life and dwarf life.

The meaning of these signals is open to interpretation. Does the movie…

Portray an engaged team of employees who love their jobs and exemplify a great American work ethic?

Show a historically marginalized group excluded from the mainstream workforce, degraded with fictional ailments to make their othering more palatable to above-ground society in the same way that, say, modern-day immigrants are stereotyped as disease carriers?

The first theory not only contrasts with the second, but also with the notion, explored in my last post, that the dwarfs are based on real-life child miners. Today, we look at the dwarfs as dwarfs.

See them at work in this classic video clip:

Watching the video, you’re inevitably left with the impression, “Walt Disney simply created entertainment — not hidden messages.”

You may be right. Just because he wasn’t trying to make a statement, however, doesn’t mean statements weren’t made.

Lost Souls, Hard Labor

Walt Disney, some say, depicted the dwarfs as broken.

Analyzing the Disney company’s picture-book version of the story1, Santiago Solis, now Vice President of Campus Life and Inclusive Excellence at East Stroudsburg University, notes that each dwarf has a near-pathological physical ailment or abnormal personality tendencies, exploited for comic relief. Doc is narcissistic; Sneezy has debilitating allergies; Dopey's unable to speak; Grumpy is a misanthropic pessimist; Happy is overly sentimental; Bashful has social anxiety; Sleepy shows symptoms of narcolepsy.

In the course of analyzing yet another picture-book version, Solis pierces the darkness that enshrouds the dwarfs’ livelihood:

“The dwarfs are depicted as lost souls, condemned to hard labor underground…Apparently, they were sentenced to manual labor in the mines as a form of castigation… Their marginalization is central to the issue of how disabled people are often transformed from human oddities to evil creatures, with some sort of unidentifiable ailment requiring persecution, isolation, and containment.”

Good Social Democrats?

Others propose sunnier interpretations, along with some unexpected color commentary about Walt Disney.

Folklore scholar Jack Zipes describes2 Disney’s dwarfs as stalwarts of American labor:

“…Through their hard work and solidarity they… maintain a world of justice and restore harmony… The dwarfs can be interpreted as the humble American workers, who pull together during a depression… It is also possible to see the workers as Disney’s own employees, on whom he depended for the glorious outcome of his films.”

Terri Martin Wright expands Zipes’ analysis politically. The dwarfs, she wrote in the Journal of Popular Film and Television3, represent American workers uniting during the Great Depression, when the movie was first released. They tacitly endorse the era’s labor movement:

They own a diamond mine, but in the spirit of good social democrats, they place little value on the jewels, valuing instead the hard work…

“Walt Disney’s leanings were socialist,” Wright tells us. “…Through the dwarfs’ work scenes, Disney was promoting a utopian alternative to the existing order.”

I believe Zipes and Wright miss the mark. Walt Disney had a reputation, in his early days, for holding his political cards close to his vest, but most accounts have him leaning left as a young man and ultimately becoming a far-right conservative. He despised communism and in 1947 unflinchingly testified before the House Un-American Activities committee, naming [video clip] former employees and labor activists as communists, laying waste to their careers.

Biographer Leonard Mosley offers a more black-and-white assessment of Walt Disney's views4:

“His politics, always conservative, became stridently rightist, with his special scorn reserved in the New Deal years… ‘It’s the century of the communist cutthroat, the fag and the whore!'' he once said.’”

As for the movie’s treatment of dwarfism, even The Walt Disney Company now acknowledges its past offenses. Following actor Peter Dinklage’s criticism about Disney’s forthcoming live-action remake, the company — according to the Hollywood Reporter’s Brendan Morrow — responded:

To avoid reinforcing stereotypes from the original animated film, we are taking a different approach with these seven characters and have been consulting with members of the dwarfism community...

Nightmares of Early Work Experience

Resentment among Walt Disney’s employees didn’t bubble up until after the release of Snow White. Is it possible that, despite emerging as an ardent labor adversary on the heels of the film’s success — and (according to Zipes and others) a workplace bully who demanded credit for the achievements of his hardest working animators — Walt Disney exalted labor and collectivism in his animated blockbuster? Such an extreme and sudden reversal seems unlikely.

In his own life, Disney relived his earliest job experiences in recurring nightmares. These are a window into his most deep-seated perspectives on work, and they compel us to reflect on how early work experiences shape each individual’s working life — including mine and yours.

We’ll step into those nightmares in a future post.

Work By Numbers

It’s old news, but if you’re wondering — after reading the story above — whether dwarfism is a protected class under the Americans with Disabilities Act, note that the EEOC in 2011 charged a global coffee chain (you know the one) after it 1) refused to provide a step-stool for a barista who is a dwarf, and 2) fired her — saying she presented a danger to others — on the day she requested the accommodation. The company settled for $75,000 and an agreement to smarten up its managers about discrimination and disability. (Read the settlement document.)

The Department of Labor throws down the gauntlet: “We vigorously prosecute violations at workplaces where workers are bound by mandatory arbitration.”

The DOL last week announced a lawsuit against a healthcare staffing company that required employees to repay earned wages if they didn’t work for the employer for three years. The employer used “arbitration clauses” in the employees’ contracts to prevent them from seeking relief in court.

“Many employers now insert — or rather, bury — these clauses in the paperwork that employees must accept if they want a job,” the DOL stated. Today, more than 60 million American workers are subject to mandatory arbitration, which were rare as recently as the 1990s.

“Workers always have a right to report illegal conduct to the Labor Department or participate in our investigations or litigation,” the DOL wrote, “whether or not they have signed arbitration agreements.”

LinkedIn Peek In

I shared a blog post I wrote for Health Enhancement Systems. My take on belonging, from the perspective of an employee wellness leader, will resonate with anyone leading organizational efforts around wellness, DEIB, or sustainability. Jump straight to the blog.

If you’re reading this as soon as it hits your inbox, you still have time to register, like I did, for Jen Arnold’s livestream “Career Wellbeing: A Forgotten Element of Workplace Wellbeing.” Tell Jen Heigh Ho sent ya.

Jim Huffman and Gethin Nadin are colleagues I admire boundlessly. Check out Gethin’s HRZone article, “If You Don’t Support Financial Wellbeing in 2023, You’re Not Supporting Employee Wellbeing at All,” which Jim shared here.

Solis, S. (2007). Snow White and the seven “dwarfs”—Queercripped. Hypatia, 22(1), 114-131.

Zipes, J. (1995). Breaking the Disney spell. From mouse to mermaid: The politics of film, gender, and culture, 21-42.

Wright, T. M. (1997). Romancing the Tale: Walt Disney's Adaptation of the Grimms'“Snow White”. Journal of Popular Film and Television, 25(3), 98-108.

Mosley, L. (1985). Disney's world: a biography. Rowman & Littlefield.