Here’s the critical clause of an employee civility policy that was ruled to be unlawful:

"Partners are expected to communicate with other partners and customers in a professional and respectful manner at all times. The use of vulgar or profane language is not acceptable."

On the face of it, the policy, excerpted from the How We Communicate section of Starbucks’ employee handbook, seems reasonable.

Civility rules are a mainstay of employee handbooks and a common subject of employee trainings. The US Equal Opportunity Employment Commission (EEOC), in fact, recommends civility training, saying, “Promoting civility and respect in a workplace may be a means of preventing conduct from rising to the level of unlawful harassment.”1

The National Labor Relations Board, however, identified something less wholesome when it ordered Starbucks to rescind its policy.

Section 7 of the National Labor Relations Act guarantees employees "the right to self-organization… and to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection…” Section 8 requires employers to refrain from interfering with these rights.

NLRB’s examples of violations include work rules that may inhibit employees from exercising their rights. [See NLRB’s explanation of Sections 7 and 8.]

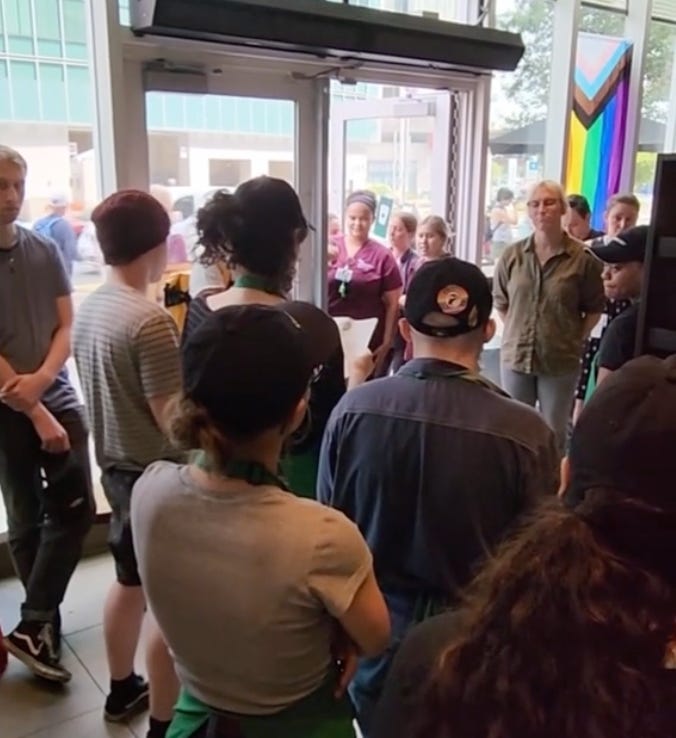

Starbucks invoked its How We Communicate policy when terminating a shift supervisor who was an active union organizer. One reason the company gave for the firing was the employee’s disrespectful and profane comment on a co-worker friend’s post in a private Instagram group.

In August 2023, an NLRB administrative law judge found that Starbucks’ How We Communicate policy and the employee’s termination were unlawful, explaining:

“Although maintaining basic standards of civility is a legitimate and substantial business interest in the workplace, as the facts here show, [Starbucks’ policy] is overly broad, vague, and is susceptible to application against Section 7 activity, especially during nonwork time. [Starbucks] failed to show that it is unable to advance those interests with a ‘more narrowly tailored rule.’”

Among a long list of remedial actions, the decision ordered Starbucks to cease and desist from “maintaining rules which employees would reasonably construe to discourage engaging in union or other protected concerted activities, including specifically the How We Communicate policy” and to make amends to the terminated shift supervisor

There’s a lot more to the Starbucks case. With help from AI, I extracted from the NLRB decision pertinent details that offer a window into the working life of hourly employees — the kind of employee experience swept under the rug in LinkedIn posts, at wellbeing conferences, and in bestselling business books. Read it here. (Or sort through the full judicial decision.)

“If a rule or agreement could chill employees from discussing or sharing information about their working conditions, it may violate the National Labor Relations Act.” — NLRB

Workplace civility policies are nothing new, but they take center stage as incivility flourishes in our polarized society (and as consultants capitalize on adjacent concepts like workplace empathy, psychological safety, and trust).

Reporting that 57% of US workers experienced or witnessed workplace incivility within the past week, and predicting that workplace incivility may “skyrocket” during election season, the Society for Human Resources (SHRM) spotlights its 1 Million Civil Conversations initiative, explaining:

“Civil behavior establishes a safe and empathetic environment where individuals can contribute their best ideas, knowing they will be heard and valued…”

Hopefully, SHRM educates its 17,000 members about the perils of misguided and misapplied work rules that risk squelching much needed and lawfully protected employee voice.

My take: Regardless of how an employer feels about NLRB rulings, civility policies that support employee wellbeing and business success should:

Be limited in scope, clear, and equitably enforced;

Be drafted with worker input;

Advise workers of their rights as well as their responsibilities.

Finally, as the NLRB requires, a proper civility policy “advances a legitimate and substantial business interest that the employer is unable to advance… with a more narrowly tailored rule.”