Hardscrabble Jobs: Character Builders or Mental Health Risk Factors?

A mistreated newsboy becomes a titan of industry

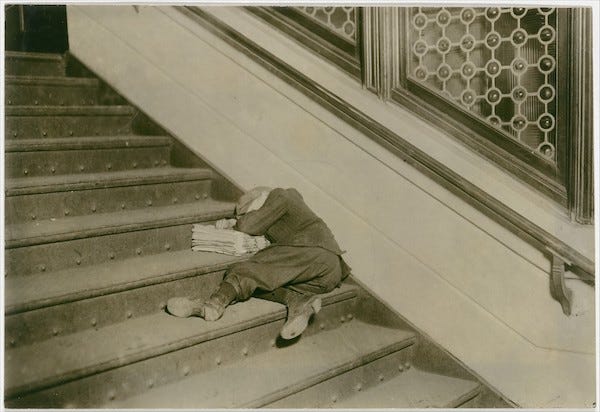

When the bottom fell out of his midwestern farm in 1910, Elias sold the land and livestock and transplanted his family to Kansas City, Missouri. There, he bought a newspaper route, commanding his nine-year-old son, Walter, to do his share of the legwork… and then some.

Walter woke up at 3:30am every morning to rendezvous with the Kansas City Star’s trucks, and later told stories of trudging through three feet of snow to deliver papers to customers’ doorsteps. Elias — an unfulfilled man known to punish the diminutive Walter for failings, “real or imagined,”1 by ordering him to the basement for a strapping — paid most of his newsboys three dollars per week, but paid nothing to little Walter.

Eager for pocket change, Walter convinced his father to order 50 extra papers he could sell on street corners after finishing his route at 6am. Under a pretense of “safe keeping,” Elias insisted the child give him the extra cash he earned. It was a shakedown; Walter never saw that money again.

The job left emotional scars. In recurring nightmares, Walter — Walt Disney as we now know him — relived his father’s rancor, as the dream plot unfolded, after forgetfully skipping a customer’s paper.

Two weeks prior to his death at age 65, he told a reporter the nightmares continued to periodically awaken him in a cold sweat.

Disney’s World: “Where Dreams Nightmares Come True”?

Though haunted by the experience (enmeshed with his relationship to his father), the newsboy job is often described as a milestone that shaped Walt Disney’s commitment to hard work — a personal value (or obsessive disorder?) that fueled his unparalleled success as a cartoonist and titan of the entertainment industry.

Ever the optimist, Disney added a fairy tale ending to the retelling of his newsie travails2:

“What I really liked on those cold mornings was getting to the apartment buildings. I’d drop off the papers and then lie down in the warm corridor and snooze a little and try to get warm. I still wake up with that on my mind.”

Character Lies in the Eyes of the Beholder

We often describe exploitative jobs — like other adverse experiences — as character-building. (Readers may infer, from Fortitude, by ex-Twitter VP

, that misery-as-self-actualization is a subtext of contemporary employee resilience-training programs.)What seems like character-building experience to the beholder may look more like harmful trauma to those in the path of that beholder’s unkindness.

We needn’t psychoanalyze Walt Disney based on his relationship with his dad or on his dreams. But nor should we accept Walt Disney’s persona as it was often projected to the public. Looking past the success and happy facades, biographer Neal Gabler presents3 a more three-dimensional portrait of Walt Disney’s work “character”:

Disney savagely belittled his employees — including his brother Roy — in front of coworkers.

Refusing to cut short a business-and-pleasure stay in South America, Disney skipped his father’s funeral.

When his cartoonists tried to unionize, Disney brought in armed guards, fired organizers, and cut wages. (He willfully crushed the careers of many of them, as I mention in a previous post.)

He was a workaholic, self-absorbed and distant when he was with his wife (Lillian) and their kids. Gabler writes: “His years of obsession [with Snow White] had taken their toll on his relationship with Lillian… ‘He demanded a lot of everyone around him,’ she said…, ‘He always kept everybody in turmoil.’ It was turmoil that Lillian didn’t appreciate.”

Understanding Walt Disney’s early job experiences, and how they haunted him, sheds fresh light on the subject of work as it pops up in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and other productions.

“One of the most striking things about Disney’s portrayal of managers, employment relations, and the everyday experience of work is how very dark and pessimistic the overall picture generally is.” – Sociologist Martyn Griffin4

More importantly, it reminds us to reflect on how our own early experiences shape our current working lives.

Coming soon (just in time for summer hiring!)… The low-down on adolescent employment: The jobs that help (and those that hinder) future working life, educational achievement, high-risk behavior, and family time. I guarantee: You’ll be stunned by the research findings. (Advise your friends and co-workers — if they’re interested in youth development, education, mental health, or careers — to subscribe by sharing this post with them).

Schickel, Richard. The Disney version: The life, times, art and commerce of Walt Disney. Simon & Schuster, 2019.

Schickel, Richard. The Disney version: The life, times, art and commerce of Walt Disney. Simon & Schuster, 2019.

Gabler, N. (2007). Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. 1st Vintage Book ed.

Griffin, M., Learmonth, M., & Piper, N. (2018). Organizational readiness: Culturally mediated learning through Disney animation. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 17(1), 4-23.

As someone with a positive first working experience as a teenager (my county library's bookmobile), I was stunned at how un-joyous my first adult job was. Long, boring hours processing insurance claims until 4:30 when the CEO read from Bible on the loudspeaker. Those were the days! Sometimes wonder if they're really gone.

I like the audio option, Bob! Is this you? I'll have to figure out how to do that. Also, a neat surprise that the young newsboy was...Walt Disney!